On May 24th, 2025, we lost one of our most insightful, trenchant writers of genre books and comics Peter David. Peter David isn’t a name that you’ll necessarily think of when you think of “comic book writers who changed the medium.” Firstly, it’s very ordinary: it’s two plain first names. Grant Morrison, Dwayne McDuffie, Chris Claremont, Gail Simone, Christopher Priest, G. Willow Wilson, the list goes on and on of people with recognizable names that mark their incredible work and make them instant topics of discussion. But with a name like Peter David, he might as well be your city’s comptroller or the accountant whose jokes you pretend to laugh at during tax time so you stay on his good side. But if you’ve been reading comics for long enough, you’re going to encounter his name and that’s particularly true if you’ve been reading superhero comics of the Mighty Marvel variety. X-Factor is a team of street-level mutant heroes that David essentially brought together and shepherded through some of the best, most overlooked, compelling drama I have ever encountered in mainstream books anywhere. Do yourself a favor: if you don’t want to read the 100 issues leading up to it, check out what happens when Jaime Madrox holds his baby with Theresea Cassidy for the first time. Have you stopped screaming yet? Welcome back, and don’t worry! We’re talking about The Incredible Hulk: Future Imperfect!

Before he was rewriting the book on what “street-level” mutant stories had to be about, though, he tackled Marvel’s biggest, greenest problem. I mean hero. He is quite a problem for a lot of writers, and even more readers, Hulk often struggles to have an ongoing book that doesn’t get handed off to another hero, and has for a long time. A lot of readers have similar problems to him that they do with Superman: the perception that the Hulk is just kinda boring when the truth is: he requires a more deft touch than his “SMASH” persona would seem to indicate. He gets stronger as he gets more angry, and while that limit can be interestingly tested, it can really only be pushed so far without really putting your back into it, creatively. If you’ve read enough Hulk books at random, that’s quite clear: they mostly run the gamut from “good” to “forgettable.” His problem is a simple one, but it’s also fundamental to his character: he’s too strong for anyone to be a credible threat to him. Yes, he tells you that on every page, but it’s a problem that doesn’t exactly go away the more he’s written and the more power creep starts to take hold. If anything, he becomes a bigger problem. It’s like some kind of Metaphor or something! His biggest problem, from a creative standpoint, is finding or inventing a villain cool and credible enough to stand toe-to-toe and really make the reader wonder: how’s Hulk gonna get outta THIS one? Better buy the next issue and find out what happens when Leader and MODOK team up!

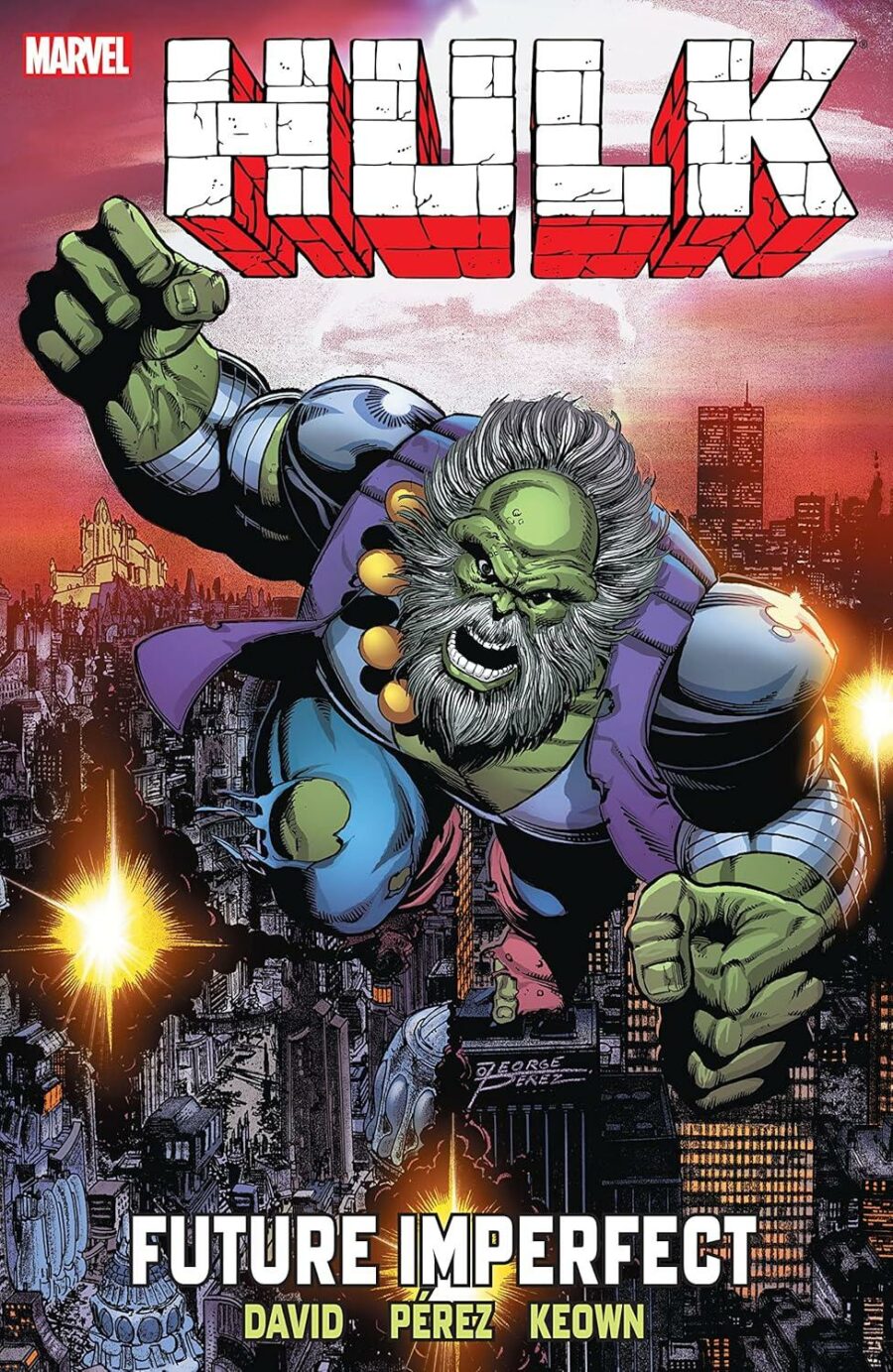

“Another Hulk” is both the least and most interesting answer to the question of a credible threat, of course, it all depends on how much creativity the writers and artists have, and how much the editors and, of course, the ever-watchful but incredibly uncreative censors and advertisers are willing to allow for. Because Peter David’s run on The Incredible Hulk, from start to stop, is all about the type of introspection and philosophizing that Ang Lee thought mainstream audiences were ready for when his Hulk movie was more about Banner than what he could smash. And nowhere is that more typified than David’s legendary story Future Imperfect. A story within the main run on The Incredible Hulk told over two oversized issues, making it about as long as The Dark Phoenix Saga. Yet talked about 7% as much, which I find baffling. Both books took place in the mainline run of their characters, Future Imperfect is technically set between Incredible Hulk issues #413 and #414, but is considered a canon part of that run. Yet it feels like a book where anything can happen. Where Banner’s back is pushed against the wall like never before, and the question of whether or not he returns is a constant refrain. It takes place in the place between the panels: where the real stories are told.

It’s a story of Dystopia, one of the last remaining cities after a third world war ruined the world over a hundred years ago. I hear you asking: why didn’t the superheroes stop it? They tried. Humanity’s nuclear arsenal put a stop to their ‘do-gooding,’ as well as the villains’ more cartoonishly fun attempts to counter it, with a quickness because, as is stated in the book: nuclear war doesn’t look like what we think it does. It’s just people dying by the billions. This is similar to the point made in Garth Ennis and Richard Corben in the intensely hopeless, nihilistic, and dour Punisher: End, but that story had the benefit of being a What-If…? story in everything but name and marketing. Future Imperfect had the impossible task of continuing the main Hulk book after it was over, they couldn’t just say “everything sucks and now our protag is dead because fuck you and everyone else, that’s why.”

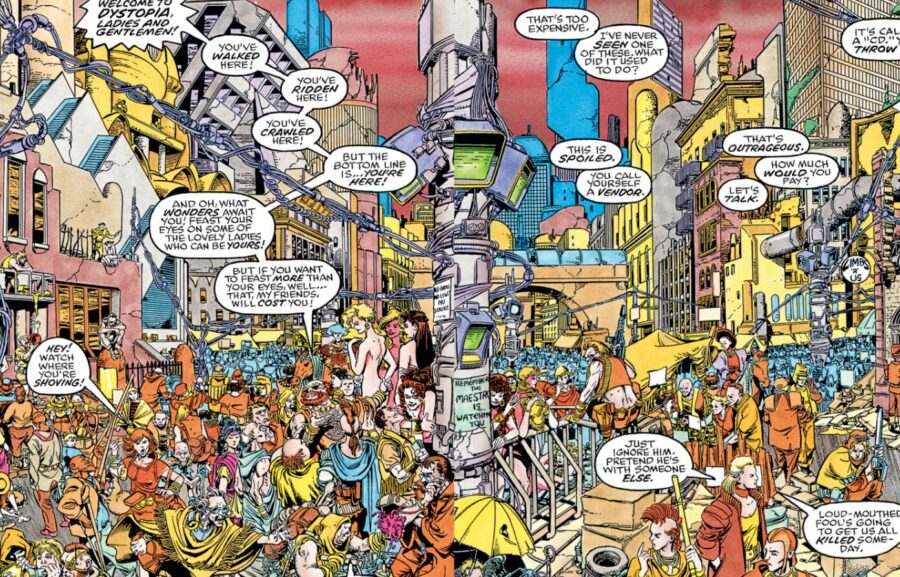

If this all sounds a bit on the grimdark side, that’s the beauty of Future Imperfect: by having the late-great George Perez to do the linework, with Tom Smith on colors, Joe Rosen on lettering, and stand-out covers by Dale Keown, the book maintains an almost manic tone of horrific and casual violence and graphic imagery coupled with a bright, cheery ’70s sci-fi aesthetic that makes the whole world feel justified. It feels like something is trying to distract you in every page and on every panel because in Dystopia: life is fast, cheap, and impossibly hard, but people are still desperately trying to enjoy themselves.

George Perez, for those who want to save a quick search, is known for his attention to microscopic detail on massive projects and doing the linework of some of the most legendary imagery of any period for mainstream comic books, including Crisis on Infinite Earths, Infinity Gauntlet, and some of the most famous covers you’ve definitely seen in the background of any movie or show that actually cares about getting comics imagery exactly right. This team, with David at the writer’s desk, constructed a world in a single two-page splash that was credible, bombastic, and enormously iconic without resorting to a bleak, dull color palette with walls of overwrought narration to communicate how bad things have gotten without doing the legwork.

Dystopia is a miserable place, but if you just look at the gorgeous art without really reading the incredible dialog, it might not seem so. It’s bright, it’s smooth, there are barely-clothed sex-workers mingling with cybernetic citizens all looking distinctly Greek or Roman without directly referencing those empires. It’s filled with a vast array of diverse, strange, wonderful people, but they’re all stressed and miserable. They’re all crammed into a massive mono-city (or Megacity, the Judge Dredd inspiration is self-evident and perfectly channeled) and they know they can’t leave because the outside is an irradiated wasteland. Only the Maestro, the feared dictator of Dystopia, and his radiation shield can keep this huddled remnant of humanity safe. And Maestro, like all tin-pot dictators, cares far more for his own pleasure and enjoyment than that of his people’s welfare.

Bruce Banner, in his Professor Hulk years, emerges into this city from a pile of rubble. Instantly, the people give him a wide berth, not just because he’s eight feet tall and built like a brick that’s also eight feet tall, but because he looks like The Maestro. He isn’t him, clearly, there are too many differences that are readily apparent. But considering the fact that we soon see Banner set upon by the authorities, and that those signs about Maestro watching you aren’t just propaganda, it’s clear that no one thinks he actually IS the dictator. Hulk smashes through the ruling authority’s cybernetically enhanced supercops, and that’s when he draws the attention of the big man himself.

This is all so that when you first see Maestro, a hulking green brute with an overgrown beard and massive mane of hair around a prominent bald spot, body adorned with jewels, robes, and other ostentatious finery, you might not immediately notice the fact that he is clearly the Hulk. Or maybe he’s A Hulk, remember: there’s more than one as well as several “spin-off” gamma-fueled powerhouses. Hey, maybe someone out there really DID think Maestro was some kind of overpowered Doc Samson that had enough of listening to everyone’s problems, and decided to solve them all at once. The fact that Maestro is a gamma-powered villain is obvious, the fact that he’s Bruce Banner doesn’t come out until the end of issue #1. Cards on the table: I have no idea if this was a great twist in 1992. It’s not shocking now, I’ll say that, but it’s well-executed so “shock” matters a lot less. I could go back and read reviews at the time, but critics are paid to look deeper into what we’re criticizing, so I wouldn’t be surprised if they “saw the twist coming,” because they were expecting a twist. But while that’s not a bad thing on its face, it certainly wasn’t a surprise in 2005, when I first read Future Imperfect, but it was still a great reveal, because it’s so satisfying. A twist only matters if the build was good enough, and Peter David, George Perez, Tom Smith, Joe Rosen, and Dale Keown constructed one helluva build.

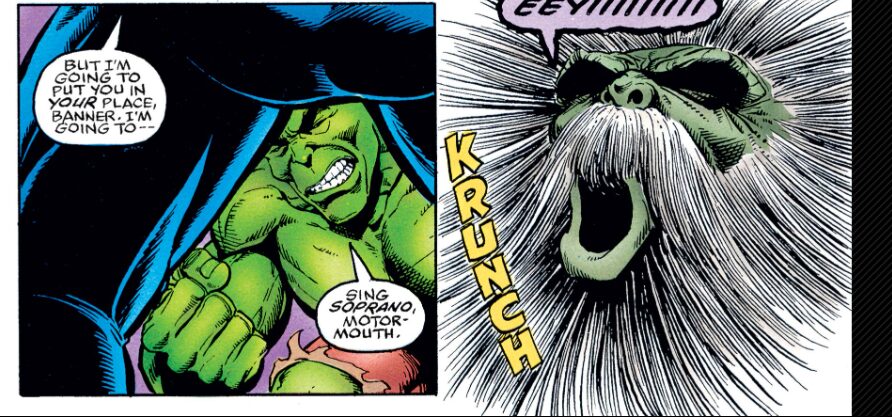

Without going over every page, I could but 10,000 words is a bit of a tough sell these days, Banner gets recruited quickly by the resistance group that brought him forward in time. Because there were no heroes nor other villains left to oppose Maestro’s brutal, fascistic rule, they had to get very, very creative to finally take a run at the king and not miss. And the only thing, they reasoned, that could stop Maestro was Bruce Banner, the Hulk, the original, no substitutes. The first fight between the two is vicious, brutal, and hard-hitting. Hulk really only loses because he places the lives of the civilians around him above his own, because he’s a hero. The dialog Peter David writes for him is perfect, making him seem detached and jaded, unimpressed by the world around him because of his dizzying intellect and impossible strength. But the moment “puny humans” are in-danger, he disregards his own safety, and the fight he’s currently winning, to save them. He doesn’t have all the answers immediately. He doesn’t pick up a gadget or a gun and use it to shoot enough people that he can save the civilians trapped under a crushed building. The Hulk does what a real hero in that situation does: punch Maestro RIGHT in the balls and start working on clearing rubble as fast as he can.

That right there is why you trust your art team. Linework, color, lettering: all perfect. And all something that even the readers can relate to, despite the planet-breaking strength of both men. Far too often, superheroes and good-guys are written to be rubes, so the villains don’t have to try as hard to outsmart them with blunt cruelty. Banner uppercutting Maestro in the dick is a perfect moment because it’s hilarious on the page, it’s brutal to think about, and it’s the smartest move if he wanted to disable the green dictator for as long as he could so he could try and help as many people as possible. Of course, Banner’s great “weakness,” his empathy, distracts him and Maestro gets the upper-hand, snapping his neck in short order. Which does not kill him. Exactly as the degenerate tactician planned. Because Maestro isn’t just a jumped-up cokehead born into opulent wealth and with political aspirations where the love of a family and friends should be, he became a dictator through sheer force of isolation and a body that ate nuclear bombs for breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a midnight snack. To paraphrase Joseph Conrad: ‘all you need to be a conqueror is brute force, nothing to boast of, as your strength is only as a pure coincidence of the temporary weakness of others.’

Everyone else died. Hulk just-so-happened to live. Maestro doesn’t know if killing Banner outright would kill him as well, Banner IS his younger self, remember. Canonically, that is true in the world of The Incredible Hulk, both as a fictional setting, and real-world comic series. He assures him, though, that should Banner try again: he’ll take the chance on multiverse theory and a timeline that split the moment Banner arrived into a future he wasn’t supposed to be in. Maestro really has been planning on fighting a younger version of himself for decades, and so far, so good. Hulk is completely incapacitated, unable to move but still able to reason, speak, and function otherwise.

There’s a scene that’s hard to describe without going into graphic detail, but Maestro demonstrates his power over Banner through a means you will not see coming with forty guesses, but it’s done well and executed tastefully enough that it passed the muster of 1992’s much further-reaching, and far more overt, censorship. It amazed me that this book came out in 1992, yet wasn’t talked about anywhere near as much in the mainstream comics discourse as Watchmen or DKR, both of which were from the ’80s. There are incredibly broad, thematic details that owe a lot to those books, and their success likely meant the team had far greater creative freedom for the team on Future Imperfect, but the book stands on its own perfectly fine. Yet despite being every bit as good as both those books, I would put it against any two issues of Watchmen or DKR and say it competes, it’s often just known as “the first appearance of Maestro,” who is an immaculately designed and realized villain, and is little more than a comics-themed pub quiz answer. And the funny thing is: if you go back and read a lot of comics from that time, there are plenty that really are amazing, groundbreaking, and stand the test of time. They’re just not as flashy and as transgressive as those two books were almost a decade earlier. Future Imperfect is violent, bleak, sexy, frightening, and it’s got a lot to say about too much power used irresponsibly, despite not once featuring Uncle Ben.

I’m not going to talk about the rest of the comic, I normally wouldn’t worry about spoilers for something that came out over 30 years ago, but in the wake the news of Peter David’s tragic passing on May 24th, I think if this all sounds good to you: you should seriously go out and read it yourself. It’s available in numerous trade paperbacks, as well as Marvel’s own comics app. It’s incredibly accessible online or offline, is what I’m saying. And it’s only two oversized issues, it will take you less than an hour.

Peter David always thought twice when he was putting his back into writing. X-Factor was always “the also-ran” X-title in popular perception. It wasn’t as violent as X-Force, not as bizarre as X-Calibur, not as important or widely read as X-Men (with all 26 superlatives) but it was one of the most consistent. The book was rarely below a 7/10, writing-wise, and often hit moments and storylines that were easily 9-10. Art often varied, but that’s the reality of a monthly title that hit surprisingly few delays in its decade-plus-long run.

David also wrote numerous novels, including some of the most well-liked Star Trek novels as well as some X-Men and Spider-Man ones that I personally think are more interesting than they are actually great. I think those latter two really prove how critical art can be for these superhero books to not have to explain every little thing, moment, and instant of what’s going on, and that’s as much a failure of the medium of the novel as it is of Peter David’s abilities as a writer. His novels are worth reading if you’re already a fan of the source material, but it really is his work in comics where he shone the brightest.

And without him, we may have to grapple with just how accurate the title of this Hulk story is, because I’m afraid our future has gotten a little more imperfect now that he’s no longer able to influence or steer it actively. But as the book itself ultimately exists to illustrate: it’s a future that still has hope in the people that live in it. However hard their lives may be, however stressed and anxious they become, how little power they may have moment-to-moment to their job, their government, their peers: they endure. They learn. They create. The world of Future Imperfect, even outside Dystopia, is well-realized and beautifully nihilistic. There are little moments scattered throughout the book where you get a snapshot of what life is like in the rest of the world, even just in the surrounding few miles around the city, and it’s a world ruled by a singular monster who only cares about himself. He regards other people as tools to bring him even more pleasure, even more enjoyment, and when they don’t? He reaches out with his enormous green fist and crushes their skull. It’s easy for Maestro to be a dictator: he’s an immortal, indestructible behemoth with a century of survival tactics in his mind. But he failed, ultimately, because he couldn’t see a path where enough people would stand together to formulate a plan to topple his decades of rule in a few days. At its core: it’s a story of the weak many overcoming the powerful single. It’s about how no matter how rugged the individual sees himself as, he cannot endure without others propping him up and helping him, even if he himself denies their help exists.

He only wanted to break Banner’s neck to continue his plan, he missed the fist heading straight for his balls, and he paid the price in the end. Even when he thought it was a price worth paying, he still failed. Not because of Banner alone, but because of the people Banner aligned himself with. The people who brought him forward to this horrible time-and-place in a last-ditch effort to even begin rebuilding and making things better, rather than keeping them as they are for the comfort of the powerful and few, the friends and allies he encountered who told him how to overcome Maestro’s seemingly impossible strength and merciless, self-obsessed mind.

Peter David knew what he was writing, what he was doing, I think it’s evident from all his best work, and even his most middling. I think he absolutely knew when it was time to throw out a 7 because he had a deadline to meet and didn’t want to risk his career on a delay, but he also always knew when he had a 9 or a 10 up his sleeve. He’s prolific, and yet so far from mediocre, that the word tastes bitter being associated with him.

Peter David may have left an imperfect future for us all, but he left a really amazing guide to make it just a bit better. Rest in whatever way you wish, sir. Your work is not forgotten.