The problem with Harold Halibut is that it’s a startlingly vivid artistic accomplishment, but in the traditional sense of the term, it’s not much of a video game. It’d be more accurate to call it an interactive stop-motion cartoon.

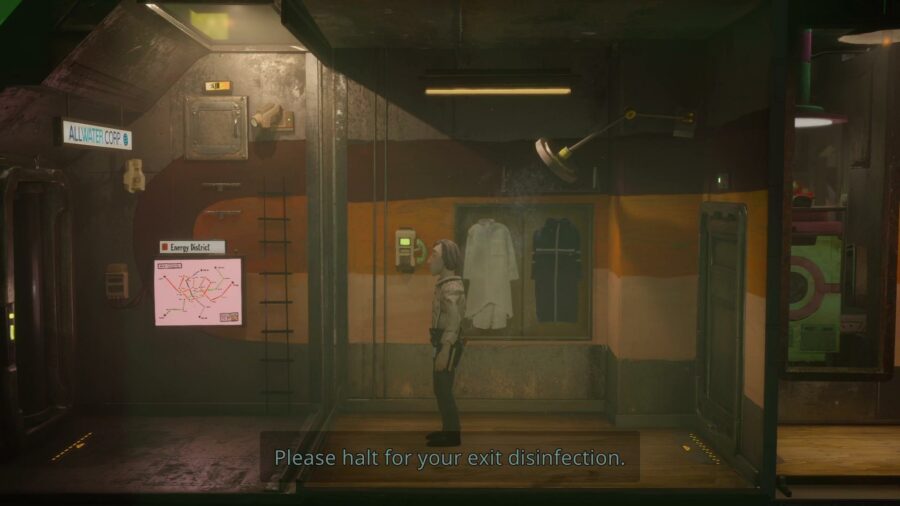

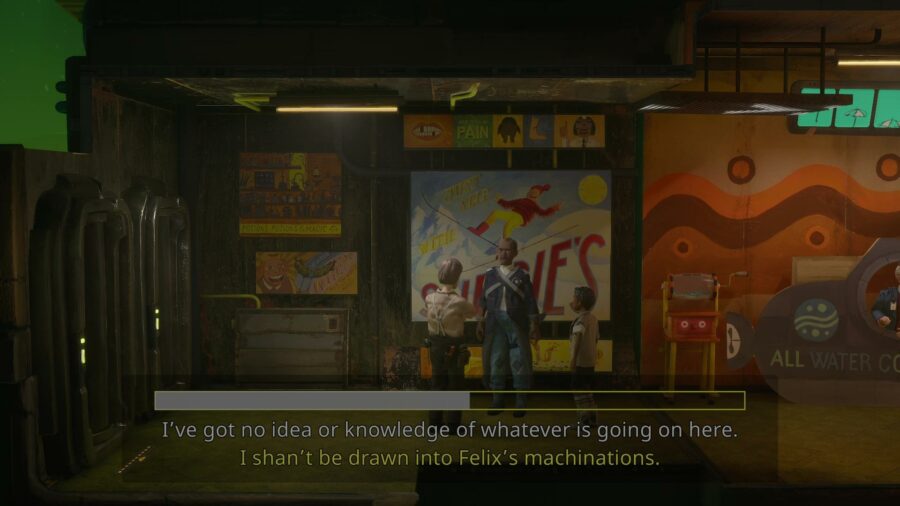

Just looking at Harold Halibut is fascinating. Its developer/publisher, the German indie studio Slow Bros, has been working on Harold for a decade. Every in-game asset was hand-made, then scanned and animated via Unity. I lost a lot of time walking around in-game to check out all the little details, like the background vistas out the window, the main character’s floppy walking animation, or the aged, boxy 20th-century tech that’s in use everywhere. You can see the developers’ effort and imagination in every frame of every location.

As a game, Harold Halibut is a dialogue-heavy adventure in the spirit of something like Syberia, where all it demands of the player is to explore and pay attention. (Some people will try to tell you that Harold is a walking simulator. Those people need to learn more words.) Your only goal in any given scene is to figure out how to reach the next step of its narrative, which usually means you have to find the one interactive object in the current room. This is rarely difficult.

All the while, Harold Halibut actively resists any attempt you might make to speed things up. You can’t skip scenes, frequently can’t skip dialogue, and can’t move at a pace above a determined stroll. Harold wants you to take it in at its own pace. Unfortunately, that pace is best described as “glacial.”

Harold Halibut is a well-meaning but slightly dim maintenance worker aboard the Fedora, a colony ship that launched from Earth in the worst days of the Cold War. Now, 250 years later, it’s stranded at the bottom of an alien ocean.

Harold’s daily routine consists of menial labor, repair work, and petty feuds with the corporate bureaucracy that runs the ship. Then, through sheer dumb luck, Harold ends up at the center of a series of events that will change life on the Fedora forever.

The opening hours of Harold Halibut are its roughest part, as its actual story takes a while to show up. The game begins with a long look at life aboard the Fedora through Harold’s eyes, in all its mundane detail. Its dramatic opening moment involves Harold being dragged off to what’s essentially traffic court.

That does give the Fedora a distinct sense of place. It’s a derelict spaceship in an environment it wasn’t built for, full of eccentrics who’ve never known anything else. Their society’s decisions are all guided by a decaying corporate administration that’s trying to play its incompetence off as an endearing quirk. Despite all that, everyone is just trying to live, and be happy, as best they can.

Harold, at the center of this, is an easy protagonist to like. He’s a decent guy who spends too much time in his own head, but he’s surrounded by a quiet, ordinary madness. Harold’s establishing character moment is being charged with a crime for what amounts to no reason, and the thing that consistently gets him in the most trouble is his inability to finish a sentence. There’s a certain Walter Mitty quality to Harold that I found equal parts appealing and frustrating.

In a roundabout way, that leads me to my primary issue with Harold Halibut. It’s a well-written, engaging story with beautiful hand-made art that sets it apart from almost every other video game on the market, and certainly from every other game released in 2024 to date. On visuals alone, it’s an incredible production, and its script is never less than decent.

The problem is that all of Harold Halibut’s strengths are in its story and presentation, and none are in its interactivity. It’s paced like a slow season of TV and gives you as the player about as much to do. You can occasionally pick up a side mission, find hidden scenes between Harold and some eccentric weirdo on the Fedora, or go play arcade games (both of which are unpleasantly reminiscent of Superman 64), but that’s about it.

Other adventure games have handled this by allowing your decisions to change the story’s outcome (Until Dawn, The Quarry), emphasizing environmental storytelling so you have to figure out much of what’s happening on your own (Gone Home, Tacoma) or splitting up the chapters with increasingly abstract puzzles (Lifeless Moon, The Tartarus Key), but little of that’s available in Harold Halibut. For most of its runtime, it’s essentially a passive experience.

What’s annoying is that I’ve been on the other side of a lot of arguments about this over the last decade or so. Some forum warriors will argue at great and terrible length that games like Harold Halibut shouldn’t be considered games at all. These people, to be clear, are idiots (why would you gatekeep a concept?), but every once in a while I play something that works as a point in their favor. That’s where I’m at right now.

That being said, Harold Halibut is absolutely worth checking out, primarily for its best-in-class visual presentation. The ideal way to play it might be in a group, where you trade off controller duty while everyone else chills out and watches its story unfold. It’s a calm, cozy all-ages sci-fi story, with satire gentle enough to surprise you when it bites. The only sticking point is that in many of the ways that matter, Harold Halibut isn’t really something you play.