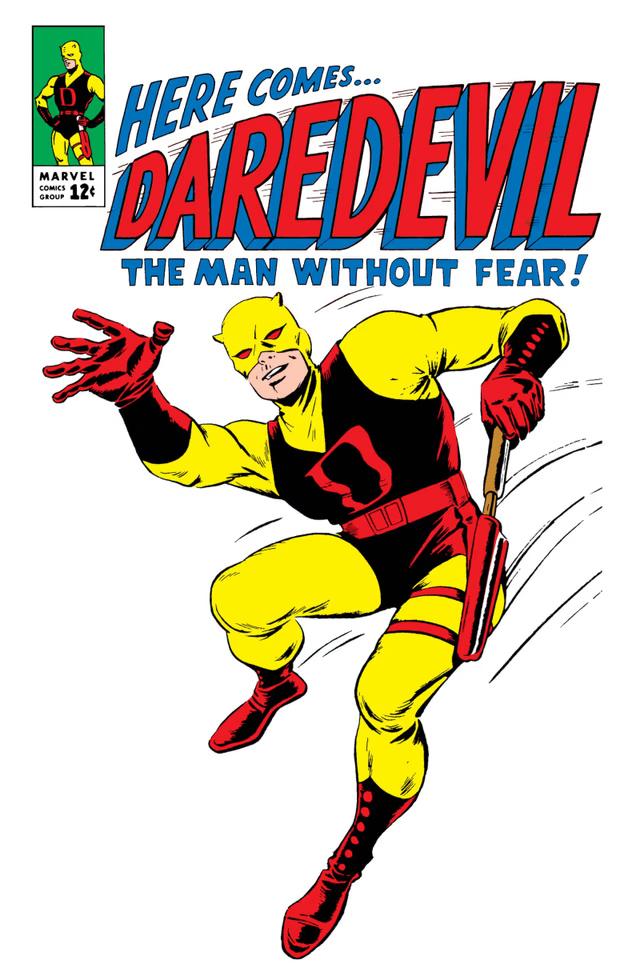

An archetype I’ve always been fascinated by in my many years on this Earth, but especially after I started work in the sales and criticism side of comics, is the hero that has to confront his ‘shadow-self.’ From Luke in the cave in Empire Strikes Back to Joker in Persona 5, few things I like more than a decent person confronting the version of themselves that still views the world in a similar way, comes from a similar background, but made different, often more selfish, choices. One of the most common recurring themes that industry experts and fans alike pointed to in talking about Daredevil was that he was a kind of “shadow version” of Spider-Man. While Spider-Man is also defined by tragedy and struggle, he is forever the bright-and-shining optimist, quipping and swinging his way through the daytime and advertising himself as ‘friendly.’ Daredevil is the opposite in most ways except for, critically, still believing the better in most people.

This didn’t happen intentionally, at least at first, the character was an also-ran more than anything else. A different gimmick and a weapon more reminiscent of a utility belt than a themed signature were all that separated the two, but then along came Frank Miller with an idea to completely overhaul the character, going down to his very DNA. And because this was a time when C-list heroes were fertile ground for experimentation, he not only gave Daredevil a retcon that actually improved him, in tying him to a new mystic origin and explaining that his radar senses were honed by a skilled ninja master, he also introduced a new concept of his motivation.

The story Daredevil: Born Again wasn’t the first time Daredevil broke through the C-lister ceiling and had a real impact on mainstream comic readers, nor was it the first time Miller wrote the character, but it is the most prominent one. And it has, like a great deal of pop-art, aged poorly in some respects. It feels like Miller is a bit less restrained behind the typewriter when it’s not his art on the page, though I wouldn’t trade Mazzucchelli’s legendary work for any other artist, past or present. However, this seems to cause some of Miller’s worst recurring tropes to rear their heads, but I don’t want to get bogged down in that too far. Because unlike his work on Batman: Daredevil fits a grittier, darker tone to a tee without fully contradicting earlier portrayals. Part of that is the restriction of working within the limits of an ongoing story, being unable to reduce the character down to an unrecognizable husk only to build him into something else entirely meant DD couldn’t suddenly start killing if he felt like it, couldn’t go off on a massive campaign to shape New York into a dictatorship under his noble fist. His world couldn’t be unrecognizable from any other in the Marvel Universe at the beginning or end of the tale, his story couldn’t wallow in the muck of how transgressive it was to see a female Robin in short-shorts or a camp, effeminate Joker terrorizing heteronormative values across the city.

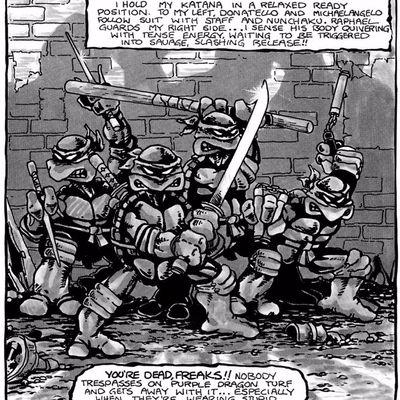

Instead, it had to be a Daredevil story first-and-foremost, and it still found room to be transgressive with subjects like drug addiction and pornography used, however shallow, for story beats, as well as a surprisingly sympathetic portrayal of villain Melvin Potter being drawn back into a life of crime against his will. And in the end: it illustrates the reality of a single individual’s total inability to enact lasting change. Strangely, though, Murdock’s fire and momentum post-Miller’s earlier stories was stolen by a very strange Prometheus in the form of four ninja mutants who were teenage turtles.

Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles creators Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird were never shy about their inspiration for the characters’ original grimdark, satirical tone. Half parody, half serious, the creators even tied the turtles’ origin into Daredevil’s: the isotope that struck young Matt Murdock as he pushed an old man out of traffic then rolled into the sewers and mutated the discarded pets. And while it was impossible to predict just how strongly the concept would catch on, looking back in totality, one can’t help but feel their success, and marketability, indirectly robbed the character of Daredevil of breaking into the mainstream outside of comics. Ninjas were doing big business in movies, but by the time the Ninja Turtles burst onto the scene, it was clear the age of the ninja being taken seriously by a mainstream crowd as a real threat were long gone. Already over-the-hill action stars were gunning them down wherever it was cheapest to film in movies, and VHS tapes purporting to treat normal men “the secrets of ninjitsu” (that isn’t a typo, it’s how it was referred to back then) were available in rental stores. A character with an origin that was, as a reminder, still brand-new and incredibly exciting for comics readers would have been laughed off the screen if intended to be taken seriously in a movie, or even in a TV show, and was already being parodied in the independent scene.

The Ninja Turtles were everywhere, but when they showed up on TV, that was the final nail in the coffin for Matt Murdock’s chances. Because while, from Marvel alone, the X-Men, Spider-Man, and even the oft-neglected Fantastic 4 got Saturday morning cartoons throughout the ‘90s, Daredevil was relegated to cameo appearances in those very shows. It wasn’t until the live-action superhero movie trend began that anyone seriously began to consider the character showing up in theaters. The trend that was started by Blade in 1998, fueled by X-Men in 2000, but truly sparked and caught fire with Raimi’s Spiderman in 2001, meant the right people with the right money and the right licenses suddenly stood up and took notice of the fact that they were sitting on “dark, gritty, mature Spider-Man.” And how could they NOT immediately rush a movie into production?

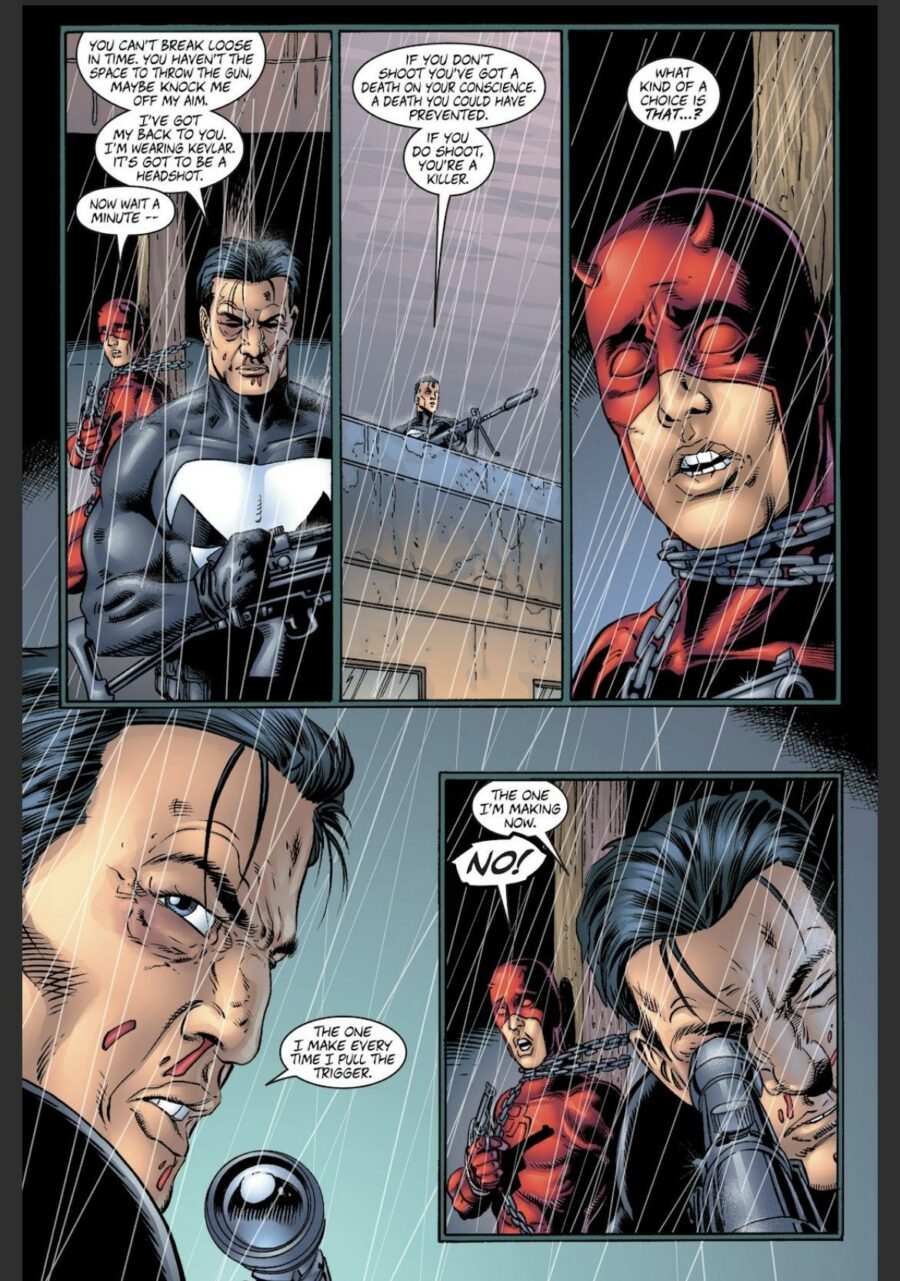

The film got a lot of things wrong, and so many people have covered it that it feels like piling on, but to keep things brief: it was and is a tropey mess with no identity of its own. It feels like an also-ran Batman script with the cave replaced by a law firm. It had star-power but the stars had little chemistry, outside of the villains. Moreover, it seemed to fundamentally misunderstand the character and his motives, rendering a vigilante with a strict code of ethics a casual murderer because that was what superhero movies did back then: try to prove how grown-up and mature they were by throwing in casual killing. Because the most pressing question being asked was: why don’t superheroes kill their villains? The answer is: the Comics Code forbade it, and it required critical-thinking and creativity to write around that limitation. It was the fantasy of power used responsibly rather than easily, and the fact that both the most vocal “fans” and moviemakers completely missed that point should have clued people in that whoever was making decisions behind-the-scenes for these movies did not understand what makes a superhero fun nor what the appeal of one is.

Daredevil was relegated to a punchline mostly because the movie flopped, but even if it had been a success, it wouldn’t have been good for the character to keep going down that route. One of the only truly excellent things that came from that movie was the special features, where industry professionals made up of writers, artists, and editors spoke at great length, and in-depth, about what made the character compelling, what made him interesting, what made him COOL. And all of it, apparently, was ignored for a movie that showed off how it wasn’t for little kids by loudly declaring, “this superhero KILLS!” and decided that was enough. And even up to the resurgence in interest in the character: he was rarely little more than a cool videogame cameo or a low-effort joke where the punchline is inevitably: Daredevil blind. And then along came Netflix.

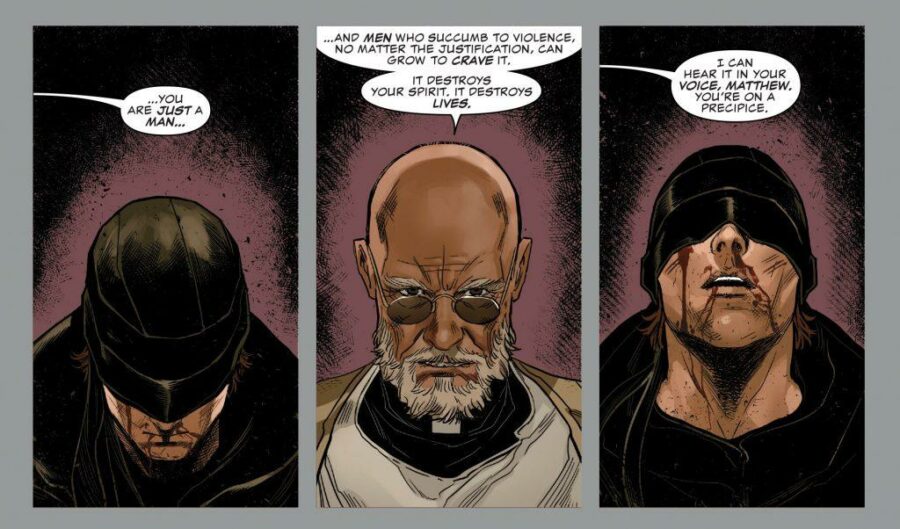

With how quickly trends and news move in 2025, it’s easy to forget just how big of a deal that first season of Daredevil actually was. Already the complaints that Marvel had grown complacent and DC’s cinematic universe seemed utterly convinced they make the “dark, gritty superhero” thing work, it was easy to write off a Daredevil Netflix show. What happened next is still recent enough that it hasn’t been papered over, but it was a fast-motion collapse of a shared universe. No one holding the moneybags had seemed to internalize the lesson that simply throwing character cameos and casual ultra-violence on-screen might work for awhile, maybe even a whole season or two, but without a strong script, long-term planning of plotlines, and consistency of characters and tone, it will simply fail to catch on as more than anything than a passing trend.

Once again, Daredevil the character was a victim of a system that didn’t seem to understand how compelling and interesting he already was. The worst thing a piece of superhero media can do is try to prove to the audience that the character “is cool, actually!” It should start from a place where the audience has already accepted that fact, otherwise it winds up like the movie: trying too hard to correct perceived criticisms of “childishness” before they’re even levelled. The character defined by his pathos, conflict, psychological realism, and struggles with his faith was perceived as a one-trick pony by the people holding the money and reading too much into low-effort feedback and social media metrics. The character was still being perceived as one that needed the allure of a “shared universe” to connect with a bigger audience. But even after a disastrous run on The Defenders, and an almost comical and inconsistent third season, the character popped in to She-Hulk to prove the audience that kept being denied what they loved about Matt Murdock were still hungry for him. And if he got to be a little bit sexy, funny, and charming? ALL the better! Fanboy backlash aside, the message was clear: there was an audience for the character, and his previous incarnation wasn’t fully burned. So when Daredevil: Born Again was announced as the next series that would feature the character, speculation ran rampant once again. Adaptation? Reboot? Relaunch? Redo? What would it be?

But here’s the thing, anyone who’s fandom started and stopped in the ’80s, maybe even picked up again as writer Brian Bendis and artist Alex Maleev redefined the character for modern comics in the 2000s, whatever the show has isn’t going to be “good enough” to satisfy that crowd. Because no show ever could be as influential as Miller’s work for the time-and-place it happened, nor could it be as impactful on the mind of a teenager still coming to grips with the limits of character and creativity, and seeing those limits shattered. And this is being written before the show comes out, I haven’t seen it. It might be terrible! It might be a season 4 that makes those first 3 seasons look brilliant in retrospect, but that hardly proves the point that the people knee-jerk naysaying were correct. Because I sincerely doubt being “closer to the source material” would fix the problems based on the fact that it never has in the past. But also because the character has undergone startling transformations and had some absolutely stellar stories in the intervening decades, up to and including the last few years.

But there’s still one gadget in the billy club that the creators can wield incredibly effectively: using the knowledge of hardcore fans to create brilliant moments of subversive storytelling. Things like the moment of Mandarin being revealed to be a fraud in Iron Man 3, the moment Karen Page isn’t killed in the church in Daredevil Season 3, Poe Dameron being shown that Han Solo isn’t an aspirational figure anymore in The Last Jedi, making Harry Osborn Venom in the recent Spider-Man games. All moments designed to make hardcore fans who claim they are immune to being surprised gasp and say, “That’s NOT how that’s supposed to work!” And most of the works get crucified for it in their own time, usually by the very people demanding to be surprised and wanting something new. Subversion for its own sake can work, when it’s trying to make you rethink what you believe a story CAN be. When subversion takes well-known and well-worn tropes and turns them on their heads, it justifies itself by making people think creatively about what is, and isn’t, possible in the established universe.

so much less compelling for both characters’ arcs and long-term storytelling than this.

Because the point of the character isn’t that he “has to save everyone all the time,” the point of the character is: he is trying his hardest to be a better person, and in the current climate of superhero media, that is a powerful message that needs to be accompanied by a powerful, effective story to resonate. Otherwise, it’s going to get lost in the shuffle and I have a sinking feeling this will be DD’s last chance to try this again with any kind of backing or budget. I hope whoever’s writing the ending has a great one in-mind. And that they won’t have to change it because some random redditor guessed it by taking the crazy step of “plotting how a well-told story would end” because Daredevil doesn’t need a shared universe or any other gimmicks to be compelling to a mainstream audience, he needs a real chance to show them just how interesting he already is.