In my approximate 15-20 years of closely following trends and discussions in the world of comic books, as they’re known in North America and large swaths of Europe at least, I’ve come to realize something, and it’s something modern superhero movies didn’t seem to learn the lessons from the failures of mainstream comics in the ‘90s: grimdark power fantasies only take one so far when trying to be “gritty” and “mature.” Mostly because, of the two major books that started the trend in superhero comics, Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, the former was intended to show how psychological realism CAN’T work in superhero comics and shouldn’t try, the other, to be blunt, takes up far, far more time in discussion than it deserves because of the long shadow it casts across all of comics media.

In the 1980s, the superhero genre seemed in desperate need of revitalizing. The narrative goes that, mostly owing to the overbearing weight of the Comics Code Authority, superhero media was seen by the mainstream as toothless, lacking in impact, and targeting young children, mostly by necessity as the various rules and regulations essentially banned anything resembling complex characterizations or moral ambiguity. And in keeping with that narrative, Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns changed all that, introducing a bevy of new readers and old to dark, mature stories taking place in “fantastical settings,” but with “realistic” characters, except there was a problem with that perception: before books like Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns, Walt Simonson, Len Wein, Steve Englehart, and Marshall Rogers had written and drawn Strange Apparitions, a dark story of madness and romance with the Batman at the center of a conspiracy to use the mentally ill as a superhuman army, and even with a particularly memorable, and wild, Joker plot involving copyrighting fish…to say nothing of the great work Denny O’Neal had done portraying the character as an exaggerated figure of darkness and terror before any of the ‘grit’ was introduced. Alan Moore himself had written several one-shots for DC tackling incredibly dark subject matter, as well as some stories that simply didn’t talk down to or condescend to the audience. This doesn’t even account for his run on Swamp Thing, or Grant Morrison’s transcendent Doom Patrol. And while these books aren’t talked about nearly as much as the previously mentioned two, they’re far more arcane and oddly psychedelic, off-putting to a casual reader. In my professional opinion, as someone who has followed trends in comics, Kraven’s Last Hunt is everything The Dark Knight Returns gets far, far too much credit for being, and it came out just two years after that book did.

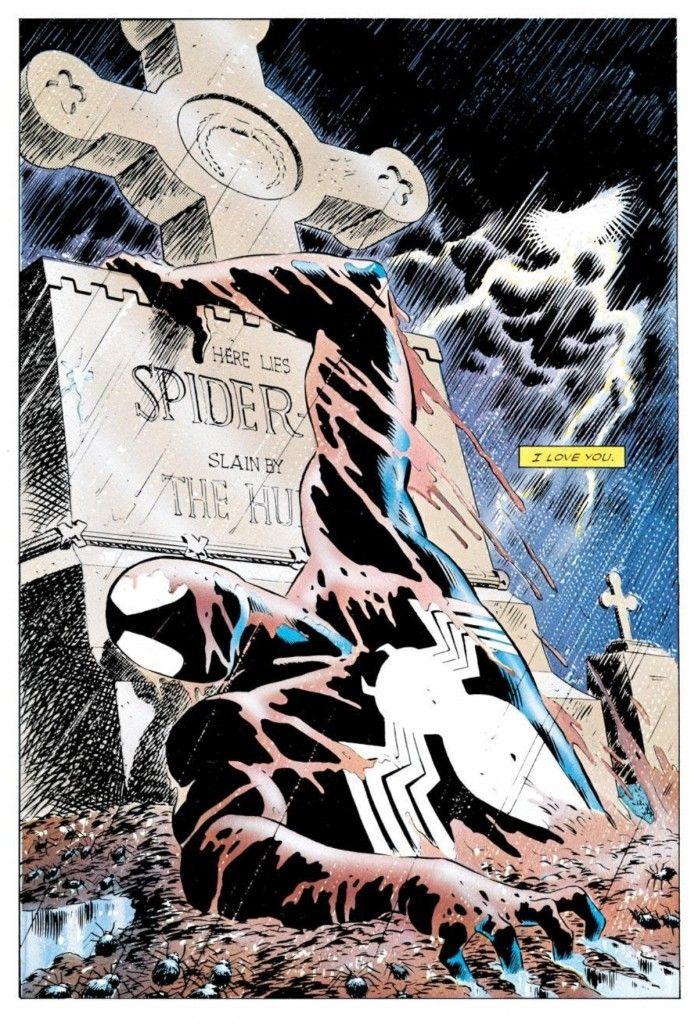

First thing’s first: I have read both books from beginning to end in the last 2 years, and I think that’s important to establish. A lot of moments and panels from DKR are memetic, and with good reason, but the book’s structure and tone overall is its greatest failing, and you don’t get that until you actually sit down and read the book, cover-to-cover. Kraven’s Last Hunt is a title that takes a well-established character, one with a history of bright, kid-friendly designs and stories, and injects just the slightest bit of grit and psychological realism to turn the character into a haunting, powerful, misguided harbinger of a vision of a darker, more lethal Spider-Man.

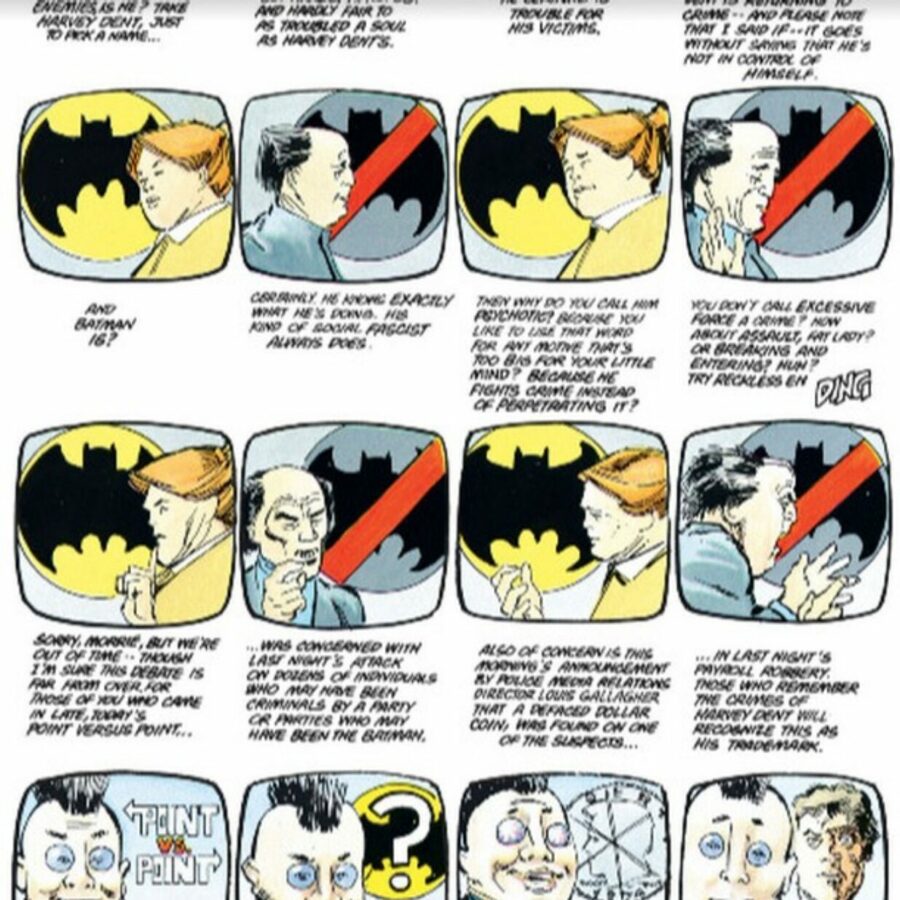

First thing’s first: I can’t deny the influence and impact that The Dark Knight Returns had when it first came out. The sales data I linked above tells the story: the book started strong and ended stronger, people were enthralled by it, and it seemed to pick up a ton of word-of-mouth in the time between the first and fourth issues. I’m not here to argue the book was actually a failure, sales-wise, or that it didn’t have a tremendous impact on the direction of the character, my argument hinges on the fact that it’s hardly singular, it was just the one Batman comic a lot of people had recently read, and that it was far more a sign of the times than a timeless classic. The idea of an old-man Batman struggling against a world he’d long ago lost control of is compelling stuff, and the art is undeniably incredible when it’s at its best, fight scenes feel impactful down in the reader’s guts, you really feel each and every desperate punch and kick as Frank Miller’s minimalist battle dialog allows the eye to traverse the page quickly, making the fights feel ‘real’ and paced brilliantly. The character designs as well have endured as long as they have for a reason, it’s when you actually try to read the words on the page that things go wrong. Putting aside the pro-fascist rhetoric espoused by side characters the audience is meant to identify with, I think the book has a problem overall with Frank Miller’s worst habits of sudden walls of text and total lack of subtlety or nuance being written off as ‘youthful inexperience’ and the best parts being credited as what he’d intended all along.

It didn’t take long for the book to become the definitive work on the character, as the likes of Michael E. Uslan credited the book as being an inspiration behind 1989’s Batman. What gets less credit, despite being no less influential, are The Killing Joke and the aforementioned Strange Apparitions, one of which has received mass-acclaim, but the other of which is lost to all but the most enthusiastic enthusiasts, at least in-terms of immediate recall of influential stories. And if you read the latter, you’ll see a lot more of its DNA in that movie’s exaggerated, gothic spires and larger-than-life Batmobile than the flailing attempt at telling a “mature” story that DKR now reads as. But because the book stood out at the time, and was something genuinely novel and fresh in 1985, it took the reins of Batman’s entire tone and character, and only when Batman V Superman came out and underperformed did the tide begin to shift in the other direction.

It was the ‘80s, and in comics: trends were bending toward extreme selfishness and Gordon Gecko and Reaganomics asked America: why should we care about others when WE can be rich and successful!? Superheroes were seen as increasingly passe as indie comics began to find their footing and get more and more mainstream attention outside of the biggest names. Watchmen never cracked beyond the top 5 in-terms of sales, but it also cost twice as much as a standard single issue at the time, so while individual sales were never record-breaking, the people were speaking loudly with buying trends: a prestige comic that treated its source material seriously could do big numbers. The X-Men had just re-debuted and even in the ‘70s, things were different. Characters were dying, metaphors were about big ideas like civil rights and emerging LGBTQIA+ issues, the X-Men tended to top the sales charts and it sent a clear message: people were ready for something new out of superheroes. Real peril and real stakes, villains with motives beyond “blowing up the ocean” or “stealing pies” that the Comics Code had kept in-check with their badge of approval. But Watchmen didn’t bear that badge, and it was lighting up the sales charts.

Meanwhile at Marvel, Sergei Kravenoff was a joke of a character. He was introduced as a borderline pro-wrestler, a hunter with an ostentatious costume (and really think about how much it takes to stand out in the field of Spider-Man villains) and a bombastic personality of someone writing a Russian character based on some Rocky & Bullwinkle reruns they’d caught one late night. He was never a heavy-hitter, he was a perfectly fine als0-ran and the book never forgets this simple fact. Spidey expects nothing from him. He’s not Dr. Octopus, he’s not Green Goblin or even an unpredictable maniac like Rampage. He’s the dude who wears a lion vest and a loin-cloth. So he’s the perfect subject for a full character reversal.

Kraven’s Last Hunt opens with a Sergei Kravinoff the reader has never seen before: powerful, determined, a grinning madman talking about the past, his ancestry, his fallen nobility and broken family, the state of Russia in-general even comes up as a reason for what comes next. Kraven has snapped after endless defeats and indignities foisted upon his noble personage. That and the suggestion that he doesn’t have long to live sets the tone immediately: this isn’t going to be a normal Spider-Man story. But the brilliant subversion comes from the fact that Spider-Man doesn’t know any of this.

Peter Parker is newly married to Mary-Jane Watson, who in this timeline is a model and aspiring actress who knows Peter Parker and Spider-Man are one-in-the-same (spoilers), and while we’d like to think she’s ‘accepted’ this dichotomy, one of the things the book does incredibly well is give her an inner-life as she senses, a spouse’s intuition, that her partner is not okay tonight. Yes, it’s still a woman worrying about her man, but she doesn’t just sit by the window and pine for him: she goes to places he’d be, she talks to the friends that they share and have in-common, you get the idea that Mary-Jane’s life exists when Spider-Man isn’t with her, and so you get to feel the anxiety that comes from not knowing where the person you love is, or even if they’re safe. And while that could normally be chalked up as silly worrying, in this case: it’s a person putting himself in constant danger for the sake of others that she’s worrying about. I challenge anyone to tell me what the inner lives of characters in Dark Knight Returns, outside of Batman, are. Even Carrie Kelley, the new Robin, hardly seems to have a thought that doesn’t involve Batman or getting away from her cartoonishly negligent “hippie druggie” parents.

One of the greatest mistakes a lot of stories like this can make is taking the main character to an illogical extreme far too soon. DKR actually does this very well, the death of a Robin caused Batman to hang up the tights and gadgets, and he watched as Gotham descended further and further into a nightmarish, crime-riddled dystopia. His mind is broken until he can simply endure no more. The flaw with that book, and many like it, is that it mistakes this extremism for being justified by the state of the world, and I think the best thing that Kraven’s Last Hunt does is switch the dynamic so it’s the villain that’s lost everything and desperate to claw it all back while the hero has to keep their ideals intact in the fact of this new, horrifying threat.

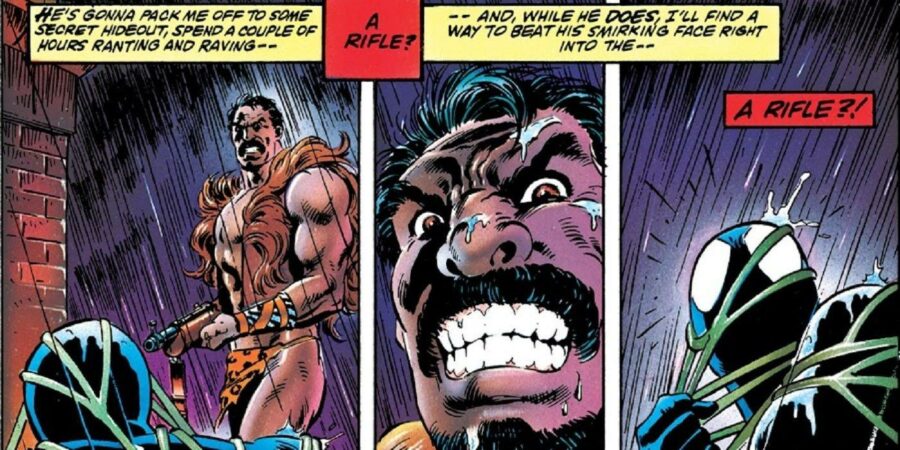

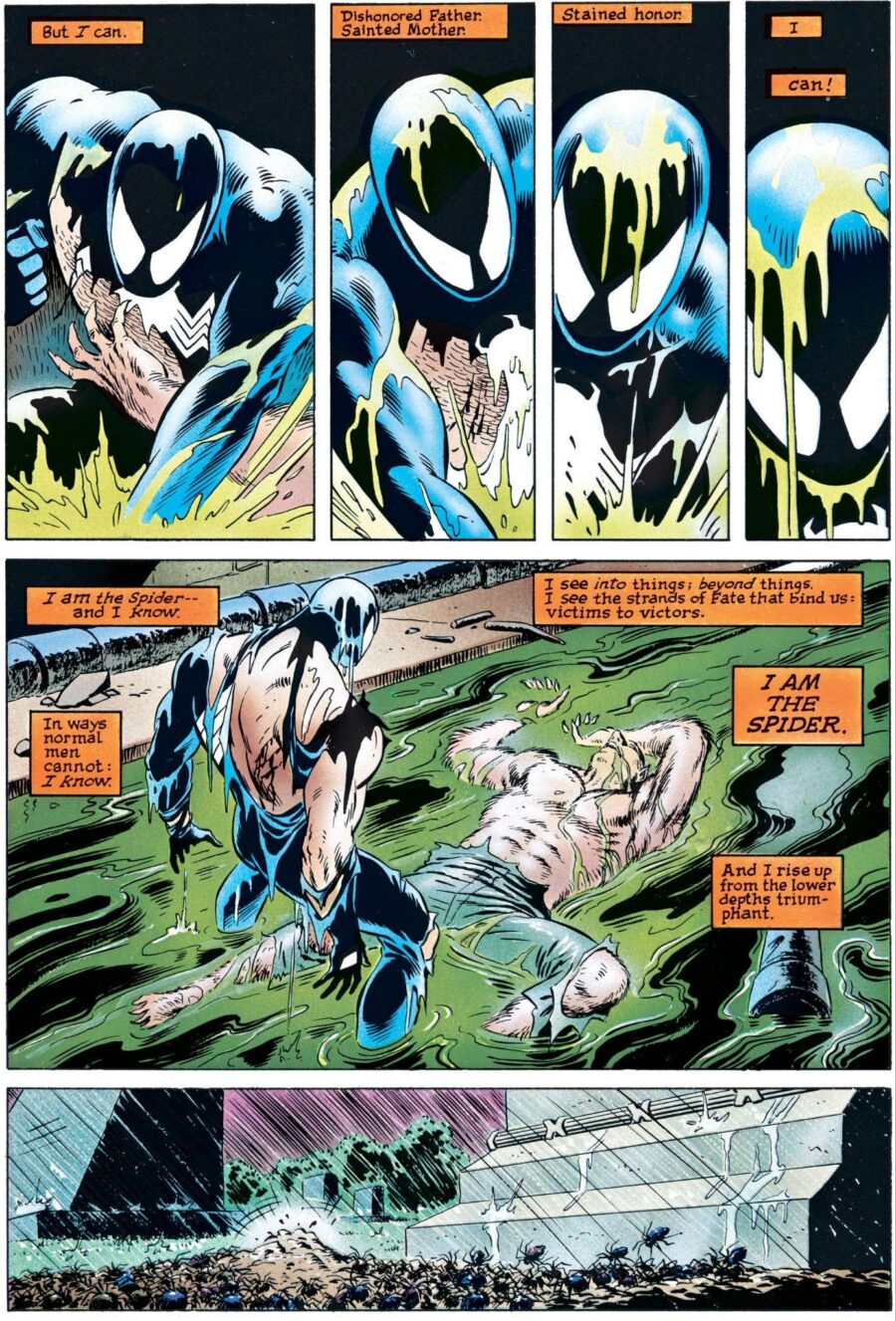

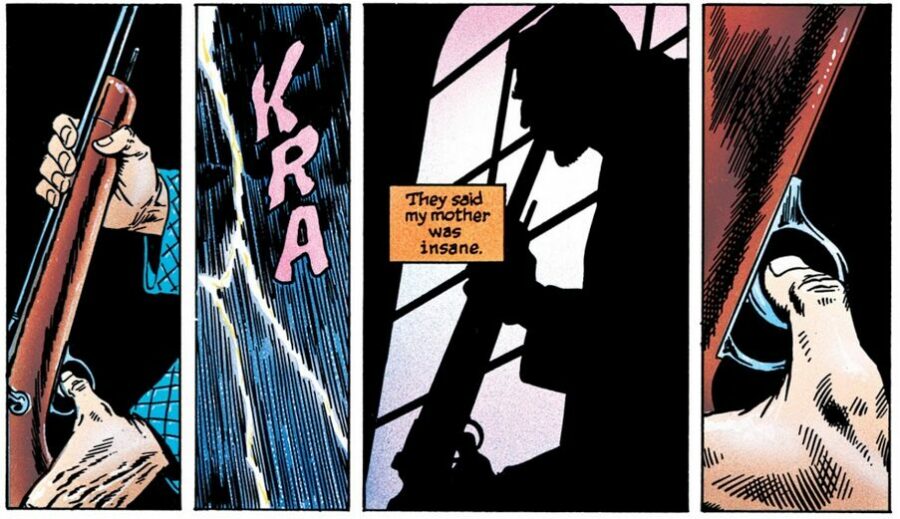

Kraven is dying, and the book doesn’t make it clear if it’s a metaphorical or spiritual death, or if he actually doesn’t have long to live. He’s last of a line of Russian aristocrats, he pines for a pre-revolution Russia ruled by a nobility of dignity and strength, or at least that’s how he perceives it. His yearning is already tinged by the rose-colored glasses of nostalgia and the book never strays into “he’s crazy, he doesn’t need to make sense” character motivation, the reader simply gets the idea that Kraven is deluded. Even within his own mind, he can’t seem to settle on whether his mother and father were upright gentry who never lost their regal dignity even as they fled for their lives or a pair of desperate, broken weak-willed cowards, shattering the moment they faced real hardship. The continued refrain of ‘they say my mother was insane’ becomes a rallying cry as Kraven breaks the rules, absolutely fucks himself up on “jungle herbs and poisons,” and does the unthinkable: traps Spider-Man in a net and then straight-up shoots him with a rifle. And this is where the book turns.

In Kraven’s twisted mind, he’s going to prove he’s better than Spider-Man. But he doesn’t actually know Spider-Man, and that is the key flaw in his plan. To him Spidey is just an emblem of his own failure and his family’s failure as well. Spider-Man represents everything from the Bolsheviks to Kraven’s own internal sense of entitlement to the capitalist system he finds himself trapped in, Spider-Man represents everything Kraven hates. So when he becomes him, he becomes a bad parody of him. The difference between hating the thing you’re parodying and loving it is often obvious to anyone outside one’s own bubble, and people immediately start noticing the more hard-edged, frightening Spider-Man. A Spider-Man that viciously beats petty criminals and kills without so much as a second thought or quip. In Kraven’s mind, violence and murder make him the better Spider-Man, but in reality: he’s everything Spider-Man isn’t. Spider-Man is a people’s champion, Kraven’s version of him is a vile, authoritarian brute and bluntly has more in-common with Miller’s Batman than previous iterations of himself. Kraven, like Batman in DKR, knows he’s right about all this, it doesn’t matter that it only makes sense in his own mind. His might makes him right. He is wealthy. He is noble. He is powerful in body and tactical in mind, but his emotional state is wavering. His psychological grounding is weak. And yet anyone who reads the book without analyzing the subtext could, and would, say: he’s perfectly rational, because his logic makes internal sense. And therefore: he believes he knows how he can conquer Spider-Man, and it’s through becoming a superior version of Spider-Man. Long before Doc Ock was The Superior Spider-Man, Kraven spent two months (in comics time) dressed up like Spider-Man, doing things his own way. And it nearly destroys the hero for the rest of the city.

It comes to a head when he thinks the way to prove his ultimate point is to defeat Vermin, a homeless man turned into a killer, cannibal, mutant rat by Baron Zemo and set loose in the sewer. In Kraven’s twisted logic: if he could defeat Vermin alone, without the help Spidey had, it proves he’s better than Spider-Man. Missing the point that: Spider-Man’s raw strength and ability to fight isn’t what makes him beloved, it’s his empathy. His ability to comfort traumatized victims and still see the good in his vast rogue’s gallery, and the admiration his fellow heroes have for him that they’ll run to his side when they see he needs help. Spider-Man couldn’t kill because of an outside force, the Comics Code Authority, but the writers skillfully weaved that limitation into the very fabric of the character: he doesn’t kill because he believes in redemption. Kraven speaks compellingly and charismatically about Spider-Man’s “weakness,” and if you take him uncritically at his word, it would be easy enough to agree with him, his words are florid and “rational” without analysis. But this book isn’t being written for you to be hand-held through it, Jim DeMatteis writes eloquently about how he tried to get this story published for so long, and how it incubated and turned into something else entirely in the waiting. How intentional it was to finally choose Kraven, a character that was a punchline, and elevate him by also deconstructing him.

In the end, Kraven easily defeats Vermin, but of course he does. Spider-Man doesn’t generally lose fights because he’s underpowered or outwitted, he generally loses fights because he holds back and tries to help the victim, even to his own downfall. Before superhero books started tackling issues of mental health, overpolicing, the role of vigilantism, and other social issues around criminal justice, Spider-Man was the type of hero who’d use violence not as a last resort, but to protect rather than attack. This influence can best be seen in the latest videogame where, even as Sandman rages through New York, Spider-Man is desperately trying to talk him down and reason with him, trying to figure out why he’s had this break rather than immediately trying to ‘take him down hard and set an example for the other scum.’ Because today’s ‘scum’ is tomorrow’s ‘victim,’ and he knows that deep down.

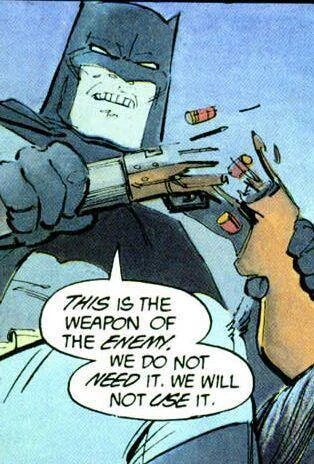

Kraven’s version is the Spider-Man that I hear a lot of people who aren’t terribly familiar with superhero characters and tropes wish for: a more brutal, killer hero. The question of “Why doesn’t Batman just use a gun” is almost as tiring a complaint as “Superman is so boring” because it betrays a lack of any attempt to engage with the character. “Why doesn’t Batman use a gun” is a perfectly fine question to ask, because it has an answer: the character doesn’t want to kill people because he believes it’s too easy of a path to go down, and has a traumatic association with guns from his childhood. A lot of people find this answer unsatisfying, and to them I’d say: there are plenty of heroes that use lethal force and guns in both major companies and all over the indies, but those tropes tend to clash with mainstream superhero stories. Trying to pound a round peg into a square hole results in stories that feel like anyone could be in the role of the protagonist, and it’s what makes DKR such a frustrating book to actually read. Batman, at one point, is even driven into a corner and forced shoot a member of the Mutant Gang, a gang of violent, drug-addled youths, in the head in order to save the life of a child the gang member was threatening. This moment isn’t given much, strangely, Batman betraying a core conceit of his character, something that’s been a part of that character for decades, and he hardly thinks about it after-the-fact. He had to do it, so it’s therefore morally correct and he never questions himself. He never has an introspective moment, despite this page being one of the most prominent in the book.

I love this panel! I think it expresses a lot about the character, about his motives, about his methods, and about the kind of message he wants to send. It’s only a pity he doesn’t seem to believe his own words, as even the Batmobile is equipped with guns that shoot rubber bullets, Batman jokingly “promising” the reader that they’re not real bullets. This is what I mean when I say: I understand the book, taken in totality, for its influence on the medium, but there are so many moments like this where it either contradicts, or has no interest in engaging with, greater themes of vigilantism, mental health, and the role of mass-media in the spread of misinformation and news. And frankly, just two years later, Kraven’s Last Hunt does all these things, so the excuse of it being the “style at the time” to have superheroes not be introspective or think about greater causes and themes is plainly, flatly untrue.

I do think Dark Knight Returns worked so well at the time precisely because it was using a long-established character like Batman as the central piece. But because of its influence on one of the first “big, tentpole” superhero films, I often heard it talked about as though it were the only book that dared to try to tell a dark, mature superhero story and I’d like to think by now, it’s clear that’s not true. By the mid-2000s, that version of Batman bore little resemblance to the character’s core ideals for the last several years, if not decades, and felt more like a cudgel to beat Miller’s perceived enemies with when he wrote dismal follow-ups like The Dark Knight Strikes Again and All-Star Batman & Robin, the latter of which is a canon prequel to DKR.

Meanwhile, Kraven’s Last Hunt is a story about how singular a superhero is, about how irreplaceable they are, but it’s also a story about a struggling marriage. About the anxiety that comes with being in-love and not being able to keep track of that person at all hours. It’s about being so consumed by your failure, you allow it to fully take over you. Kraven isn’t a better Spider-Man because he’s more brutal and efficient, he’s not even a better Spider-Man because he can defeat someone Spidey couldn’t, he’s worse in every way because, very simply, he’s allowed his failure to define him. Throughout the book, Peter Parker wrestles with the people he’s lost, Gwen Stacy and her father, Uncle Ben, the recently-deceased Ned Leeds, and while he grieves and processes their deaths, he comes through the other side of this hardship better and not willing to be consumed by it because he still has a life worth living. Kraven’s version is far more emblematic of the Batman we’re supposed to be rooting for in DKR, DeMatteis even directly makes this comparison in an interview.

When Kraven fully hallucinates, when he goes on a spiritual journey to ‘kill the spider’ and thus become it, he believes he’s succeeded. I think Kraven failed in that awakening. I think the spider of his failures and fears consumed him and he’s now a walking avatar of those failures, a malformed hero with a broken, twisted motivation who doesn’t realize his own flaws and hypocrisies because he’s too obsessed with himself and his own story having an ending that ‘makes sense’ in his own mind, even if it doesn’t to anyone else.

Kraven dies by his own hand at the end of the book, and I think it’s the perfect punctuation mark to end on. There’s an element of tragedy to it, the fact that it was his madness that drove him to it, that Spider-Man couldn’t break through to him, but in Kraven’s own mind: there’s nothing else to accomplish. He ‘bested’ Spider-Man at a game in which he set the rules. His suicide isn’t portrayed as noble or indealized, it’s blunt without being graphic and the reader is left with the very real feeling that Kraven could not endure another failure. Ironically, Peter Parker is left ultimately confused and unsatisfied. But he goes home to a partner that loves him, to friends and allies that support him. All Kraven had was the hunt.

In that sense, I think Kraven’s Last Hunt specifically has had an incredible impact, particularly on modern Spider-Man stories. But even going back to something like Maximum Carnage, which has its own issues, the story is ultimately about Spider-Man not giving in to the trend of extremism mistaken for maturity. A trend that was largely started by a pair of books in the mid-80s that posited the idea of telling a “gritty and real” superhero story. Watchmen is a book about how psychological realism doesn’t belong in a fantasy setting, not fully at least. DKR was about “how cool it would be if Batman just cut loose” the way Superman does when he’s the villain. But the writer failed to understand that someone with power using it without thought or empathy, no matter how noble they purport to be, isn’t a superhero. And both books were taken by the mainstream as “look how cool it is when sexual violence and a high death toll are in superhero books!” This isn’t to say those stories can’t or shouldn’t be told, they absolutely should, but it goes back to trying to pound a square peg into a round hole: the entire medium of mainstream superhero comics turned on the point that “this one comic book inspired a really, really good movie” and I’d argue the opposite is actually true: often the power fantasy that superhero comics allow the reader to engage with is the fantasy of suddenly gaining power and using it to help rather than harm. And I can still see DKR’s influence in works like Tim Burton’s Batman or the Nolan trilogy, I just wish I saw it portrayed more as a villain’s journey to delusion and self-aggrandizement rather than a “logical motive” that will make their extremism “make sense.”

Dark Knight Returns managed to craft a Batman so unrecognizable from the perceived ‘issues’ with the character, that he reads more like a villain in another Batman story. Like Owlman or the bleak, twisted Thomas Wayne from Flashpoint: a Batman that has lost his heroic side to tragedy and isolation. Dark Knight Returns begins with a lonely Batman striking out against a world he no longer recognizes. Kraven’s Last Hunt starts with a villain losing his mind fully and making it the hero’s problem. But while the former ends with a Bat-cult forming around a fascistic leader rather than an anarchistic one, with very little commentary on why that’s a good thing, the latter ends with Spider-Man returning to Peter Parker’s life to live it. The world we live in has changed, and that will always change how art is interpreted. But I think stories of heroes being granted sudden power and understanding that it doesn’t make them superior, but fills them with responsibility, is far more compelling than someone calling themselves a hero while they fight only for themselves and break their own code when it suits their wants.