For the next couple of weeks, whenever I see an inanimate object behaving oddly, I’m going to wonder if a schim did it.

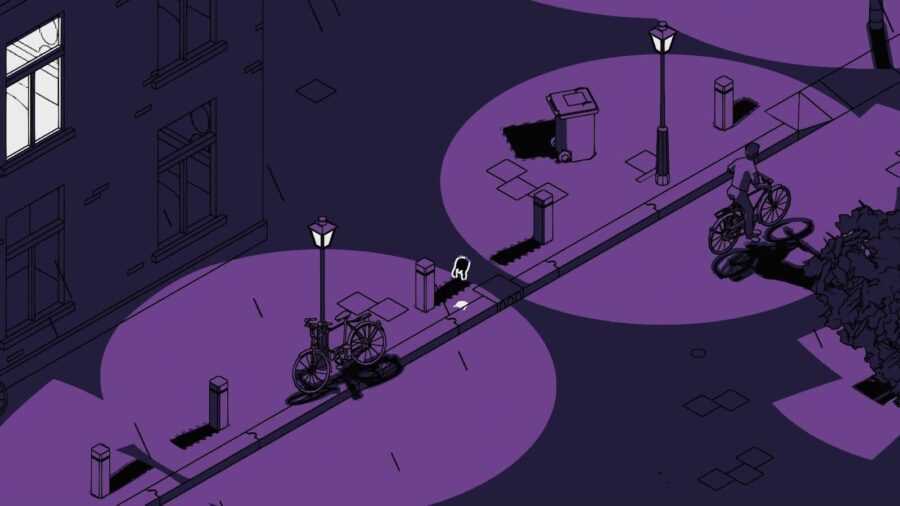

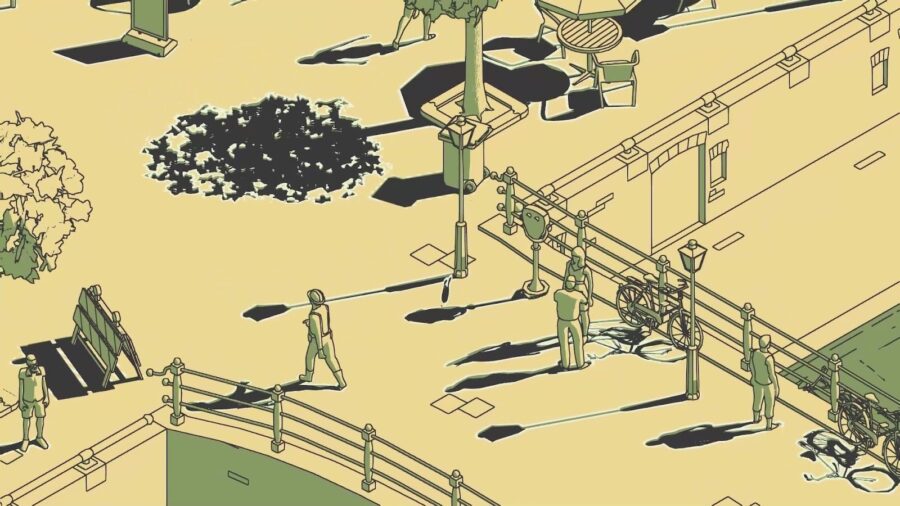

SCHiM is a new puzzle-platformer from a Dutch 2-man dev team that looks like it was made with a grant from the Netherlands’ tourism bureau. You spend much of the game hopping around rotoscoped animations of beautifully walkable urban neighborhoods, full of bicycle paths and happy pedestrians. If SCHiM had ended with an ad to “visit scenic Amsterdam,” I wouldn’t have been surprised and I might have booked a ticket.

The titular “schims” are little invisible creatures that live in shadows. Schims can influence things and people when they stand in their shadows, but that influence is limited to honking horns, startling birds, or the occasional sneeze. They’re as common as houseflies, but no one seems to know they exist.

You’re a schim who’s been hanging out in the same guy’s shadow since he was a kid. One day, that guy hits the bad-day hat trick: he gets fired, gets his bike stolen, and accidentally severs his connection to you. That leaves you on your own to try to get back to your host as he works to put his life back together.

There’s a joke in here somewhere about how SCHiM would be a really easy game if your schim’s host was even marginally less functional. Almost as soon as he gets fired, he moves most of his stuff into storage, downsizes his apartment, and starts using his free time for social activities and hobbies. If he’d just gone into a three-day depressive fugue on his couch like a normal person, SCHiM would be about 20 minutes long.

Instead, you end up chasing this guy around the city for 62 levels. SCHiM is a relatively free-flowing platformer where you can navigate freely between any shadow in the world, but can only survive for a couple of seconds in direct light. If you screw up, you immediately respawn in the nearest shadow with only the faintest hint of a death animation.

The stakes are low, the music is chill, the visuals are simple, and the colors are muted. SCHiM has a few tough levels and a couple of tough post-game challenges, but is otherwise 100% based on vibes. This is made to calm you down. Mostly.

Your goal in each stage is to chase down your former host, but it’s never as simple as that. He’s constantly on the move, as is the city around him, which turns mundane city scenes into a potentially dangerous obstacle course for your schim.

Sometimes you get additional challenges in the form of moving people, vehicles, or objects, so you have to quickly jump between their shadows as they travel down the street. That much is basically Frogger, and it’s the easiest part of the game.

The more complicated parts of SCHiM are when you have to take control of objects in your environment. Most of the time, all you can do while you’re in a shadow is shake the related object, or maybe make a person sneeze.

A few objects provide additional abilities, though. Clotheslines turn into trampolines, you can use parasols as slingshots, and sandwich boards become catapults. There’s one early sequence where you need to navigate through a warehouse by using the equipment to adjust or create shadows, because fortunately, all schims are forklift-certified.

What impressed me off the bat with SCHiM is its flexibility. When I say “any shadow in the world,” I don’t mean the shadows that are visibly labeled for that purpose. No shortcuts have been taken. You can fit your schim into any shadow, no matter how small or narrow.

As a result, while there are clearly intended paths through each of SCHiM’s levels, it leaves the player with room to mess around. There isn’t a lot of reward for exploration, outside of a few collectibles and the occasional hidden event or achievement, but it can be fun on its own to try to find your way into the far corners of each map.

On the other hand, that looseness does lead to the occasional disconnect. There are moments where SCHiM wants you to be more precise than it’s set up to permit, especially if you’re trying for some of its more challenging achievements. You’ll need a few levels to practice your schim’s jumping before you get used to how it works, especially when you’re trying to go very short distances or leaping over tall objects.

As I noted before, the penalties for screwing up are so low in SCHiM that missing a jump isn’t that much of an issue. It’s just a little irritating, which in turn interferes with the chill mood that the rest of SCHiM is working so hard to create. Some of its levels want to be a relaxing, interactive music video, while others are a G-rated take on Super Meat Boy. None of them are that difficult, but there’s a tiny identity crisis in SCHiM’s margins.

SCHiM is undeniably visually striking, short, and inventive, as well as a calming overall experience. The first level is also one of the most ambitious presentations I’ve seen in an indie game in a while, in ways I keep wanting to compare to Richard Linklater movies. It might be a little uneven and repetitive, but it’s still a decent way to kill a weekend.